Reading time: 7 minutes

The cost of housing is rapidly on the rise in nearly every corner of the country. In fact, over 11 million renters pay more than half of their incomes on rent. Today, in my first insights report, I’m going to explore the dynamics of a certain aspect our nation’s affordability crisis – the increasing unaffordability of older homes in high demand cities.

It was long the case that renters and home buyers could find affordable options in older housing stock throughout many great neighborhoods and communities. Renters could often find vintage but well-maintained apartments, and first-time home buyers could find houses with great bones in need of some TLC.

But these days, even fixer-upper homes are selling at nosebleed prices, neighborhoods with character are experiencing tremendous pricing pressure and displacing long-time residents at ever-increasing rates, while rent increases on 30- and even 50- year old apartments are outpacing those seen in new apartment buildings.

The interesting and maybe surprising fact is that the prices of old homes are strongly affected by the cost of building new homes.

So why have so many communities been experiencing such changes? It could be, as Joe Cortright has observed, that we have a shortage of cities. In the context of urbanization, this shortage does explain the nearly universal increase in existing housing in limited urban places across the U.S.

Like other private-market goods, housing is governed by the law of supply and demand, with pricing following the same dynamics as widgets and Twinkies and subject to consumers’ willingness and ability to pay. But an important difference between housing and Twinkies or widgets is that housing is a necessity and a right. Moreover, housing often represents the biggest single expenditure made by families; and increases in the cost of housing without commensurate increases in income significantly harms a household’s financial stability.

“Housing is not an ordinary commodity. It connects adults to jobs, kids to schools, and families to community institutions. Having to uproot and chase housing affordability destabilizes bedrock community institutions and families.” Portland, Ore. Mayor Ted Wheeler at Up for Growth Housing Underproduction report release event in Oregon.

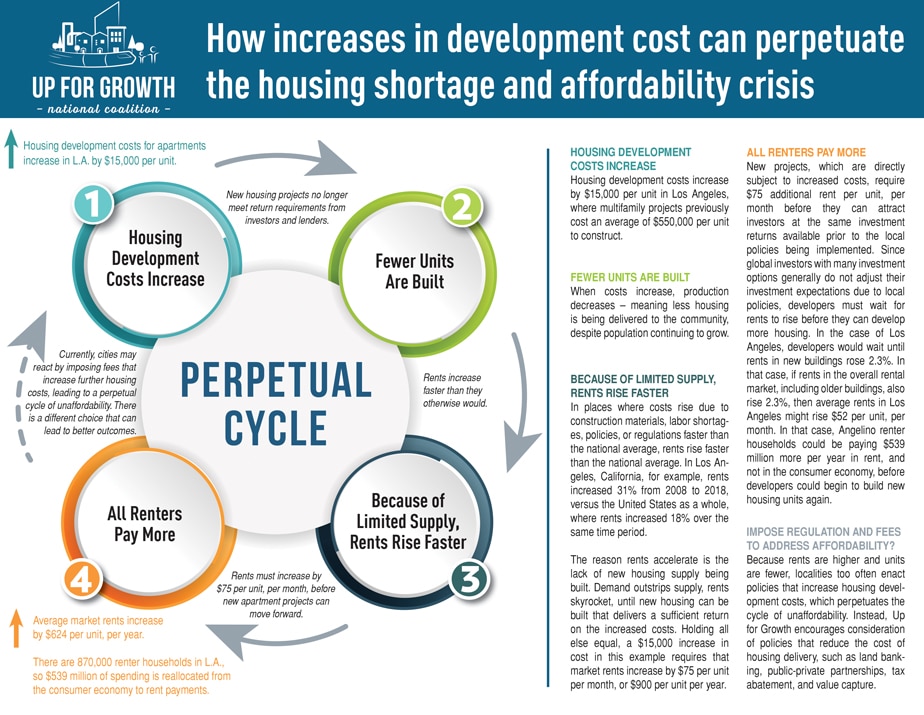

Like a producer of any private-market good, a housing developer must achieve a certain amount of return to justify financing the project. This means that increasing production costs ultimately threaten the delivery of housing. If the return required by the developer’s funders cannot be achieved, the project will not get built. If new housing isn’t getting built, there are fewer units available, leaving the same number of buyers competing for fewer and fewer units, including older homes and apartments. Prices rise in this scenario.

When the cost of housing production rises, either prices go up to cover the costs or fewer homes are produced – it is seldom the case that developers can prove to investors that they can raise prices in the near term, so projects stall or get canceled. In a high-demand environment, when developers produce fewer housing units, everyone is left competing for a smaller pool, driving up the cost of existing housing.

At present, we are simply not building enough housing in our existing cities to meet current needs. The cost of constructing new housing in our established cities often stands in the way of delivering new housing.

The inescapable fact is that increasing the cost of new development leads to higher prices for all renters and home buyers. New homes determine the price of old ones. The owner of a nearby older home needs to charge noticeably less than the owner of a newer one, or else most prospective residents will choose the newer one instead. But the more expensive it is to build housing, the fewer new houses get built, which means the price of older homes are no longer kept in check by the competitive pressure from newer homes, and so prices rise. Conversely, if the next available home can be delivered at a lower price, the affordability benefit will be felt by the entire housing market.

“In almost every American city seeing rapid growth, housing becomes a game of musical chairs. We end up with more people than housing units and when the music stops (or the rent increases), the unlucky are left homeless.” – from the House New Democrat Coalition’s “Missing Millions of Homes” report

The good news is that many of the costs of delivering new housing can be directly influenced by public policy. The Obama White House’s September 2016 Housing Development Toolkit; Local Housing Solutions from Abt Associates and NYU Furman Center; the Room for More report from SPUR; and, the Effect of Local Government Policies on Housing Supply from the Terner Center at UC Berkeley are just a few of the many reports that detail how communities and their elected officials can impact the cost of housing.

To achieve our shared goal of housing affordability in high demand cities, let us proceed from two basic understandings. First, in a housing crisis like our current one, governments should seek to promote more housing production, not less. Second, if governments needlessly make the production of housing costlier, they are making the rent or purchase of housing – regardless of age – costlier.

It sounds simple, but it is no doubt true: when you increase the cost to build housing in a high demand market, you increase the cost of all housing. Our current set of policy choices has broken our housing ecosystem, but it could become much more functional with a new set of policy choices that encourage rather than discourage new housing.

While functional markets won’t solve every problem associated with housing affordability in our cities, focusing on lowering the costs to build needed housing across the income spectrum will go a long way to contributing to broader housing affordability – a principal our leaders would be well-served in heeding as they seek to solve the housing challenge.